I have a good relationship with my past and future selves. I mean, we get along pretty well and we often give a hand to each other. I should probably use the singular first-person instead of “we”, but I want to emphasize the plurality of my different selves across time—don’t worry, we’re not schizophrenic yet.

Talking to yourself

What does it mean to talk to my selves? When you are “talking to yourself”, it usually implies that you are internally deliberating, in the current moment: it is just a way to put words on an ongoing reflection. Sometimes talking to yourself is how you rationalize your thought process, for example when you are formalizing arguments to support a decision you have to make. It can also become a habit where you just mutter to yourself for no reason when you are alone—if you do often mumble in your beard, please try not to creep people out too much.

Well, in this article I am not talking about this type of self-discourse. To be more accurate, I should probably talk about “writing to your selves”. Indeed, I am interested in how you can communicate with yourself across time, and text is the most natural medium to stretch a deliberation in time. Most people simply talk to their future selves by writing a journal, notes, reminders, or even letters to themselves.

Writing to your selves

When you write a journal, you fix on the paper your current state of mind, and you forward it to an undetermined future. At any point in your life, your future self will be able to open the journal and read its contents. Congratulations, you have just created a one-way channel to talk with your future selves! Most of the times, however, a journal is not intended to be read at any specific moment in the future: the mere process of writing down your thoughts, and knowing that they are accessible, is beneficial—even if you never re-read most entries of your journal.

When you write a letter to your future self, the intention is more explicit. You usually fix a date at which you will reopen the letter, which makes you able to directly talk to a specific future version of you. For example, if you write a letter to be opened one year later, you already have a rough idea of the range of possible worlds in which you will open this letter. You can thus address specific issues, and even ask questions such as “since last year, have you finally achieved this thing?”.

When you open the letter at some point in the future, you will be able to think in the shoes of your past self again: feel your old worries, your interrogations, your vision of life, and then you can bring your new experience to answer them. Interestingly, your old self might be wiser than you on some topics: maybe you simply lost sight of certain resolutions or forgot to focus on something that matters. In this case, the letter will be a helpful reminder to get back on track and keep some consistency with the long-term plan of your life. In other cases, you will be able to dismiss some old worries or decide that past resolutions are now irrelevant, and you will happily close some chapters of your life to keep moving on.

These two methods—writing a journal and sending letters to your future self—are well-known and can seem a bit romantic or heavy to put in place. In a more practical way, you can send very short notes to your future self in order to achieve your daily life tasks: a grocery list, a reminder on your phone, a calendar are efficient means of storing information that will need to be accessed at a later point in your life. There is no deep introspection going on there, just a convenient technique of managing your life.

Information transmission and cognitive load

It is interesting to think of it under the angle of information transmission. Technically, you don’t have to write a grocery list in advance each time you want to buy something: you can just keep it in mind, and try to remember it once you are in the store. Instead of putting an alarm on your phone to remind you to pick the kids after school, you can mentally monitor the time and remember the task when it is the moment to do it. Unfortunately, our memory is fallible: unless you are extremely well-trained, it is hard not to forget some items on the grocery list or miss a couple of appointments. Writing down is then an efficient way to transmit this information to the point in the future when it is relevant.

Even when we are able to remember things, it helps to write them down instead. Discharging some content out of our working memory is a way to reduce mental load. You can experience that when you have to handle a lot of different tasks simultaneously. When you try to keep all the tasks in your head, it feels messy, busy and overwhelming. But as soon as you write them down on a piece of paper or in an application, you get rid of this cognitive burden—you move the content from your brain to your list—and you have more power to serenely tackle the tasks on the list one after another.

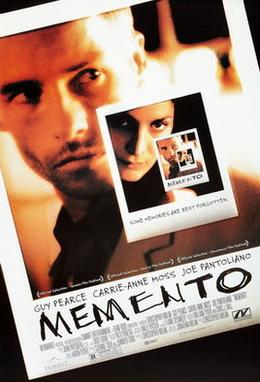

Memento film poster

In the film Memento, the protagonist (Leonard) is suffering from a traumatic mental disorder that makes him unable to form new memories. In order to keep track of what is happening, he is using a system of polaroid photos, notes, and tattoos. Roughly every few minutes Leonard’s short-term memory is wiped away, so he relies on these clues sent from the past to reconstruct the picture of his life. Even if you and I have probably more memory than Leonard, we are inherently limited and have to outsource some mental load out of our own heads. Our journals, to-do lists, and reminders are Leonard’s tattoos and photos.

Talking to your past self?

At the beginning of this article, I was talking about both my past and future selves. So far, I’ve only explained how to talk to your future selves through the transmission of information across time. Is it even possible to talk to your past self? You cannot send information back to your previous self since it would violate the laws of physics. As a result, we cannot use information transmission to give a meaning to “talking to your past self”. However, we can find another interpretation.

When you talk to someone, you are not just giving them information. The mere fact that you are talking to them is meaningful, and the whole emotional connection that you are building is having an impact on both parties of the conversation. This emotional bond changes both the way you perceive yourself and the way you perceive the other. In the case where the other is your past self, we can see an interesting pattern emerge.

Let me first give a basic example. Last year I set an item on my to-do list application, reminding me to cancel the subscription to some insurance company. I had totally forgotten about that: firstly because it is always hard to remember small chores that stretch on long durations, secondly because I did no effort to remember the deadline since I knew it was stored on my list. When the notification popped-up one year later, I instantly recalled the details and accomplished the task. In addition to the information transmission, the notification itself triggered other emotions in me: I felt a mental proximity with my past self, like when you hear the long-forgotten voice of someone you used to know. When a friend gives you a piece of advice or a trick to accomplish a task, you are grateful to them. It might seem a bit ridiculous, but after reading my reminder on that day, I paused for a moment with a slight smile on my lips and felt gratitude for my past self.

More generally, in my daily life, I often stop to contemplate my surroundings. I admire the broader context of my existence, and sometimes wonder: why am I here? I then think about the people, the social structures, the nature that make this possible. I also think about my past self, who worked hard to make the conditions of my current state of being come to life, and I am grateful for my past accomplishments. This is not a mere self-congratulatory stance: I truly appreciate the work done by my past self, which does not presume anything yet on the achievements of my current self. On the contrary, instead of staying in a state of complacent admiration, I work even harder for the sake of my future self. This is just an example dealing with one emotion, gratitude. In practice, the relationship with your past selves spans across a wide spectrum of emotions and deep layers of interpretation.

An ancient scroll

But what is the point of talking to your past selves, since they cannot hear you anyway? The answer is twofold. Firstly, remember that each time you are talking to someone you are also acting on yourself, no matter whether they hear you or not. This is why it is still worth writing a journal even if nobody, including you, will ever read it.

Secondly, your past self is not like any other third-party: it is a part of your intimate history. Each time you call a memory back to life, you rewrite it. Each time you talk to your past self, you reactualize it. You make the story real again and you reinterpret it. Think of it as a palimpsest, this antique scroll where the original writing has been erased to make room for newer writing. While your stream of consciousness stretches across time, you are constantly reading and rewriting your palimpsestic memory. As on an ancient manuscript, some old traces always remain visible under the recent stories: talking to your past self is not a monologue, it is a journey through the echoes of half-forgotten songs.

Emotional connection within your identity across time is natural to some extent because we are defined by an ever-evolving continuum of thoughts. However, I believe that it is crucial to consciously strengthen this bond with yourself to shape a harmonious identity across time. Give a hand to your future selves by transmitting them useful information when they need it, like Leonard in Memento, and cultivate a rich relationship with your past selves. In this intricate path of intertextuality, don’t forget that no stream of consciousness stretches forever. Like every story, the story of your life, that you have been writing and rewriting, will need a full stop: Memento is just the first half of Memento Mori.